Struggling with "Scenes" — Playing 'Follow: A New Fellowship' by Ben Robbins

Some storytelling games require more narrative sense than others. What do we do for players with less experience with improvisational storytelling?

Making Great Scenes at your Game Table — a series

Preface: Everyday gamers don’t always know how to make great scenes

Ending out scenes with ‘Scene Breakers’ and resolving the scene

Adding ‘Minor Scenes’ to add action and movement to our story

“Can you tell me, Socrates, whether virtue is acquired by teaching or by practice; or if neither by teaching nor practice, then whether it comes to man by nature, or in what other way?”

- Plato’s “Meno”

Ben Robbins of Lame Mage Productions and Microscope fame recently put out one of his GM-less storytelling games for free: Follow: A New Fellowship. I’ve written a bit about running Lame Mage games, and my players love them. I’m a big fan of being able to just break one out at the table with no prior planning and ending up with a killer storytelling session that stretches my creative muscles and gives my table new experience.

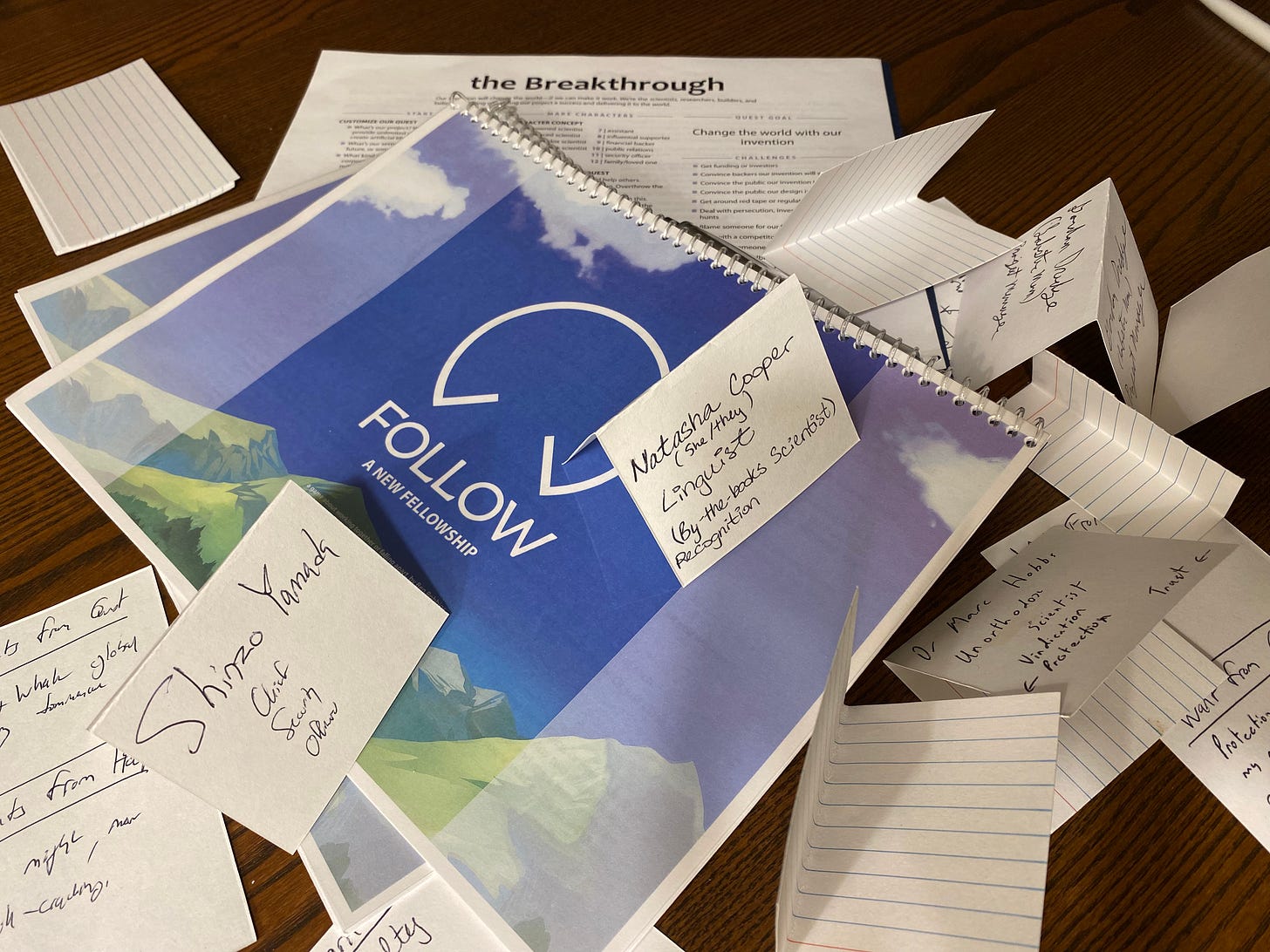

In Follow, 3-5 people pick a quest, develop some characters, and narratively chart out a short campaign’s-worth of plot using light mechanics and guided brainstorming. Take a look at the quests!

My team went with ‘the Breakthrough,’ because it seemed like something we couldn’t just accomplish with most typical RPGs. We sat in silence for a while trying to figure out our quest concept until one guy said “What if we were trying to talk to whales?” Pretty quickly, we were in the year 2090 at an underwater research base avoid the Mad Max-style global economic and ecological collapse, trying to decipher strangely intelligent whale activity and do the plot of Arrival on the ocean floor in a race with the Japanese to harness Whale Power.

The most fun part for us was generating characters and relationships. We spent far too long cry-laughing at the network of needs and interconnectedness. In story-driven games, this is often my players’ favorite part.

What an amazing time! I use “roses and thorns” questions to solicit feedback from my players, and my notes are filled with roses like “Very hilarious and ridiculous” and “it was incredibly fun.” But most of the thorns came down to a single issue:

Everyday gamers don’t always know how to make great scenes

Every part of Follow has a clear procedure — "Pick two complications and flesh them out…” or “when resolving a challenge, draw two red stones and reveal them both if…” And then we get to scenes. Scenes have a lot of incredible guidance about how to set them up well, but at a certain point you’re meant to just “play and see what happens.” One of my players, someone who is often more nervous around improvisation, said it succinctly:

“It’s very difficult to just come up with a scene that both advances the plot and gives us a chance to develop or reveal something about a character, and to improvise that.”

See, I have incredible players. But they aren’t creative writers by trade or trading. They enjoy PbtA games, but aren’t steeped in a play culture of shared narrative, and they’re often GM’d by someone (myself) who is mostly learning them from books and Actual Plays. I’ve got professional creative experience, but my other players this weekend were in fields like technology, or public service, or textiles, or just walking dogs. Their creative ability is unquestionable. Their creative training is mixed.

Ben Robbins has other games that are much structured top-to-bottom, like In This World, which is a very procedural game. If you look at a record of a game of In This World, complete with its own notation system, you can extrapolate exactly what happened in the game session. It is like cooking a great meal with a robust recipe.

Follow more provides you with ingredients and guidelines, and then sets you to cooking. Don’t get me wrong, the guidance is damn good, stuff like:

Two to three characters per scene is ideal.

Don’t hesitate to tell us what your character is thinking, even if it is something they would never say out loud.

When in doubt, end your scene earlier rather than later. Shorter scenes are better than longer scenes.

Again, my players are creatively brilliant, but they don’t have the scene-writing experience or professional skills to incorporate this advice on the fly; to do things like feel out when a scene has run on too long, or act boldly to declare that lots of time has passed between their scene and the last. I found myself giving reminders like “Hey guys, make sure the scene is about what your character is doing to address the challenge at hand,” or “Remember, this is ultimately a scene about X character, let’s try and figure out what they’re thinking, or feeling, or revealing about themself, or struggling with.”

I ran into this problem with Kingdom, too, when I ran it. Specifically, I’ve found that when dealing with an in-game crisis, the scene people often come up with is “my character and everyone else are at headquarters having a meeting about the crisis.” In fact, working out free-form scenes has been a problem for us since we played a particularly roleplay-heavy D&D 5e campaign of Wild Beyond the Witchlight: not knowing when to call for a scene, not knowing when to end it. It’s just something that’s very hard to do without a recipe or procedure.

I wonder if this might be the uncomfortable truth: These games are possibly much harder to be “good at,” at least comfortable in, for people with less experience with fields like creative writing, improv theater, or just tons of these kinds of games.

The best tool to combat this when we ran Follow was Consequences (which maybe should actually be called “Complications”). These are free-form opportunities for players outside or inside the scene to throw monkey-wrenches into a scene to give players something to respond to creatively, or to add drama. My players love the invitation to step into the GM seat in just this way, and they thrive in games with “Devil’s Bargain” mechanics that introduce this formally. And I think anyone thrives at the simple game of “Here’s a problem. Make up a solution!”

Still, I wonder if the rules text could have added a little more procedure.

The big caveat: We did get better at it.

As with Monster of the Week, or Kingdom, or Brindlewood Bay, or any other games that stretch my players’ muscles a bit beyond our traditional D&D roots. Just when we were reaching the end, we went “Wow, I feel like we’re finally getting the hang of it.”

And so perhaps a procedure isn’t needed? Perhaps it’s just something that requires practice, or is bound in with natural ability a little as well?

I’m still seeking the answer. It appears to be true that this is more the case with some games than it is with others. As a GM, I’ve worked at developing the skill, but as I’ve moved toward shared narrative responsibilities, the question is how I can help my players skill-up on this as well.

Side note: I wonder if this is related to a similar problem I have, wherein we play narrative games that are meant to be “about the characters,” but end up abstracting the actual quest faced by the players. As one of my players put it: “I thought we were going to be learning to speak to whales, and instead we spent most of the game like, dealing with potential war with the Japanese.” More on this in another post.

In the meantime, I’m running Follow again soon, or maybe even In This World as soon as next week. And in some other news…

The Roaring Age is coming!

Most of my spare time lately is in layout for The Roaring Age, which is out of copy editing and is trying to reach your hands in the next few weeks. Bear with me folks. In the meantime, there’s an itch page to look at. Let me know if you have any questions!

This is a very thoughtful article. As a player, performer and teacher of improv comedy, ending the scene remains the hardest part of improv. In narrative RPGs starting and ending the scenes are both challenging.

The concept of plateaus may be helpful. When the players feel like they are no longer advancing the story the narrative scene has hit a plateau. In an RPG scene plateaus can be detected by boredom, distraction or frustration. [insert excellent example here].

A plateau indicates the exploration has run out of creative juice for the scene members. The routine needs to be interrupted. This interruption can be a hot new idea or by ending the scene.

The biggest enemy of ending a scene is expecting a punch line or pretty narrative bow. Scenes can just "end." This might be a case of not letting perfect get in the way of a literal done.

I've had a few thoughts about scenes in RPGs recently, and your post prompted me to reflect a bit more on them. This is where I ended: https://fourlettersatrandom.blogspot.com/2024/09/scenes-in-rpgs.html

(TL;DR - RPGs generally get a bit muddled when it comes to scenes, as they sometimes use the term but don't define what they mean. In games where players frame scenes, I find it really helps to know what my character wants from a scene.)

I'm enjoying your followup posts as well.