Using Kingdom to flesh out factions in a D&D campaign: Successes, experiences, failures

Including feedback from Kingdom/Microscope author Ben Robbins himself

My weekly D&D game hit a sort of chapter break recently, and we had the opportunity to try something new: using a story game to build out a part of the lore. The party has spent the past few months seeking the Emerald Enclave as a sort of end-game ally.

My problem is, the Emerald Enclave as presented by the default lore is an absolute snooze — generic fantasy tree-huggers. I wanted a hyper-secretive, star-gazing sect of druids and operators that serve as a sort of extra-planar defense force for the mortal realms. And I wanted real player buy-in, deeper than you get by just telling players "These guys are like... really epic. Globe spanning and suspicious."

Enter: Kingdom! For those of you who don’t know, Kingdom is from Ben Robbins, the famed creator of the gold standard collaborative worldbuilding games Microscope, Union, and the upcoming In This World. Kingdom is the game that handles Faction/Community/Settlement-building.

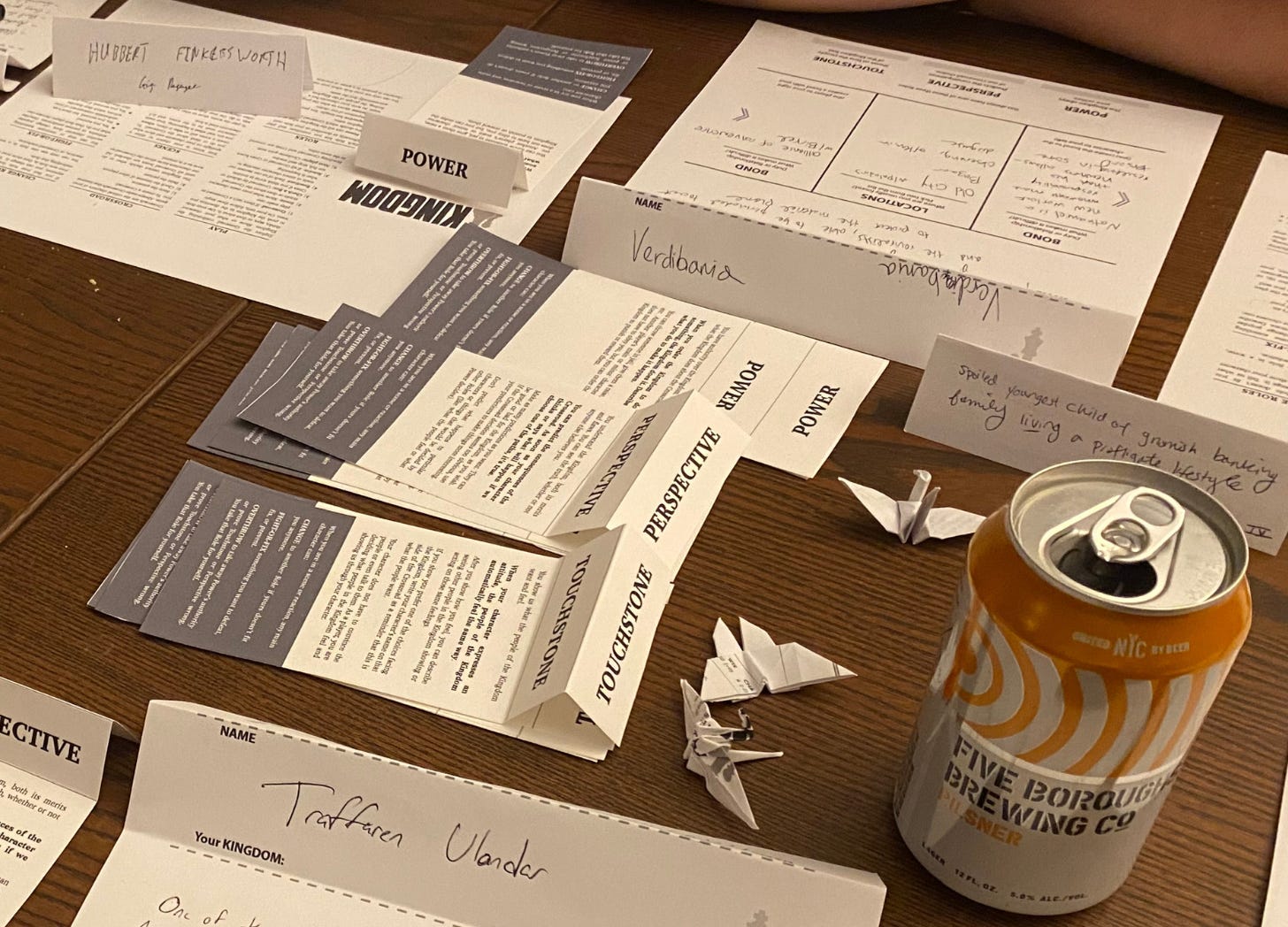

My players are real D&D 5e die-hards, with not-a-lot of story game experience. In addition, it's a bigger group than recommended. Kingdom is best with 3-4 players, I had an initial whopping 7 players, but two cancelled and I ended up with 5. I also got the illustrious Mr. Robbins to weigh in with some helpful advice, all of which I heeded, most of which was essential.

In short, it was an incredible experience, met my needs, and is highly recommended. So long as I, as a GM, was able to give my players an untouched section of the lore for them to be free in I was able to achieve:

An epic, complex history that my players all understand out of experience rather than memorization.

A plethora of characters and events more diverse and complex than something I could have easily generated on my own, especially ones that break with traditional tropes and cliches.

A series of meaningful explanation as to WHY that organization has its particular quirks and characteristics. (now my players understand why the organization is paranoid about outsiders and humans without just seeming arbitrarily weird or racist, for example)

Best of all: my players had a great time, and really enjoyed themselves.

Anyway, here are some things I learned from running Kingdom:

Fewer scenes are often better

In Kingdom, each "crossroad" has as many check-boxes in the progress clock as players+1. I thought to reduce this number for a large group, but the illustrious Mr. Robbins advised that I not cut down the number of Crossroads check-boxes because the result would be that not every player gets to invent a fresh scene for every crossroad.

But, even when characters didn't create a scene, they have many opportunities to get their contribution in, like their appearances in other people's scenes, or reacting to a scene (which is basically having a little solo-scene). By the time we get to player number five, that player's probably been in two scenes and had four reactions so far. We probably know what their response is to the crossroad, and do most of the other players at this point. They didn't set the stage for a scene, but they've had between 5-8 opportunities to act as their character regarding this crossroad. By the time their turn came, they were like "Now I have to start a scene? But I just did like three..."

And so, with a five-person table, we whittled each crossroad down from six check-boxes to four, and the game went much more smoothly, without us going "do we... need another scene here? Sounds like we're ready to go..."

Designer feedback: Upon reading the above few paragraphs, Ben Robbins wrote:

I totally get that "isn't this Crossroad pretty much done?" urge, but there's an interesting thing that happens if you just keep doing the scenes: things that seemed settled get riled up, and you discover more trouble and conflict just because the characters keep interacting. That "quiet period" at the end can lead to surprising results.

Upon reflection, this definitely works out.

Epic scale is tougher

Kingdom is a game designed to be played at the level of an organization — could be a nation, a megacorp, or something as small as an anime fan club. Our kingdom was an epic, continent-spanning organization, and I believe this made scenes much tougher, because often players gravitated toward scenes that were more like "We're standing around at home base, talking and deciding about the future like generals from afar." Once you get to three of those in a row, it's a total bore.

I don't think this would be a problem if you zoom in on a smaller level, dealing with small organizations of skilled workers, or people with personal projects, or jobs of important details. It's easier to quickly create a compelling scene when your options are "laboratory, wellness room, lobby cafe" than when you have your pick of "floating castle, distant city necropolis, hidden vault of treasures." It becomes harder to zero in on dramatic scenes, and also to imagine how everyone is constantly both all over the globe and in regular scenes with one another.

Designer feedback: More from Mr. Robbins:

What you say about epic scale kingdoms can definitely be true, because the players have to be comfortable describing big jumps in time and space between scenes if you want to use the whole scope. The farther apart the characters are, the more you have to work to frame them in scenes together, but once you get the hang of it it can be awesome. "It's a week later and I've summoned you to the bridge of my battleship hanging in orbit over your homeworld."

One good foil is a blessing

I was worried going in about playing a story game with a group of people who like to be do-gooders and go-along-to-get-along. But I've got one player who, often in my games, plays the ruffian, the shifty character, the player who makes the most trouble for the party. In this game, he really shined. He made a sort of palace-intrigue warlock who fairly quickly began to sow discord and lead a rebellion.

So while the Enclave saw success after success, by the end of the third crossroad, he had created a violent fractuous situation, leading to half of the characters exiting, and the other half remaining to clean up the mess — a fantastic moment in the organization's history.

Story games bias certain types, or at least require them

The two of my players who cancelled were some of the people at the table with the best narrative sense, generativity, and interpersonal initiative. It probably goes without saying, but where certain games are a little more personality-agnostic, story games really do require a few people present to have a certain level of interest in being “storytellers.”

Every D&D table has people who are more passive/reactive — who love their particular corner of the game, and chime in when it's time to fight, or time to pick at the lore, or whatever their favorite thing is. These people don't seem to relish a game where, every 30 minutes or so, they're responsible for coming up with an entire scene idea and making decisions on behalf of the whole fiction.

That’s all I’ve got, folks! Thanks for reading.

As always, thank you to the game’s original designer, you should buy and support all of his various worldbuilding games at Lame Mage Productions. They’re superb. I imagine I’ll be trying more of his games and reporting back here in the future.