Varieties of Scenes in TTRPGs

Across every TTRPG I've seen, there are basically six types of ways the text will guide you in structuring your "scenes," if they offer guidance at all.

I’ve written a great deal about structuring scenic play in TTRPGs, and have started to create a master list of these posts here.

What do we mean by “scene” here?

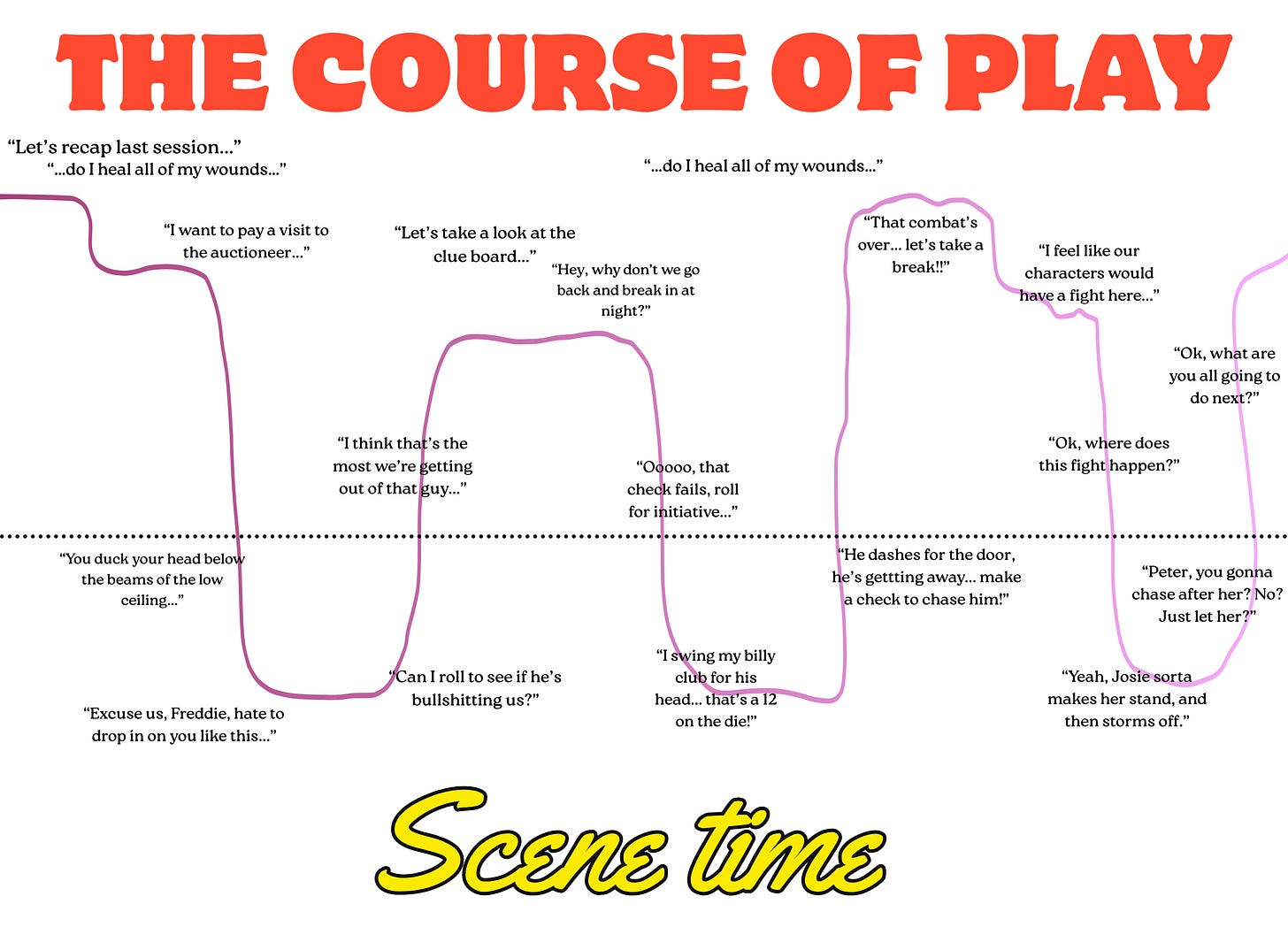

Scenes are a special pillar of our play, common to most roleplaying games. They are distinct from time spent tinkering with character sheets, discussing our plans out-of-character, or engaging with mechanics that resolve actions or shape narrative. There is a distinct mode we drop into that you can call “scene time.”

When we’re in “scene time,” we drop away from viewing our fiction from a birds-eye view and enter near to our characters and their perspective. This can include playing out a scene in real time, play-acting, or simply narrating our characters’ actions and behavior.

Players generally know they’re in scene time when they begin thinking “in character” moment-by-moment. Scene time begins and concludes. We enter in, and we exit. Often, these bookends come and go without ceremony.

Many games properly called “roleplaying games” don’t formally mention scene play at all — the treasure-hunting, monster-killing dungeon crawl comes to mind. But for many games, scenes are the pillar of advancing play and resolving conflict, and we enter into scenes, structure them, begin them, and end them in all of our sessions.

So what do our rule books and written guidance have to say about how we spend this time?

In my reading, it seems most games don’t provide anything resembling a “structure,” but rather relegate the scene-making process to game master skill, or offer general advice on what techniques serve players well in spontaneous scene-making.

Many games don’t mention scenes at all, leaving scenic play as a self-evident pillar of the game experience. In these cases, the book presumes that when it’s time to have a scene, your instincts will kick in and you will know what to do.

My interest is in games that attempt to do more for GMs and players by adding structures and guidelines. It is a growing trend for games to explicitly name scene-play and give proper scaffolding, particularly for those games that have scenes as the primary arena for players to challenge one another and create satisfying game outcomes. Guidelines and processes are great tools for inspiring players and equipping them for success.

In my research, there are generally six approaches to structuring scenes, though some games use a hybrid of two or more structures. I’m not a big fan of taxonomies, but I couldn’t help myself:

The Foundation Scene

In these games, the procedure for scene-making is simply an outline for some information you can use as a starting point. The GM is advised to establish or ask for a list of ingredients, such as “Who is present,” or “Where does this scene take place?”, or the motivations of the various characters in the scene. Then, improvised play begins, often with general advice or guidance— but no further procedures — for how to develop and end the scene.

This is the most common starting place for building a scene, and for many games, there is little else in the way of structure. But it is common that this simple approach of asking “Who, what, where, when, and why?” is married with another of the following approaches.

The Framed Scene

Framed scenes flow from an initial moment, inciting incident, or provocative image from the GM. Like the foundation scene, the formal structure of the scene is just a launchpad, with improvised, free-form play following this initial frame. Framed scenes use initial circumstances to focus scenes on key moments in the narrative, directing a scene’s energy and improv by clearly identifying the conflict and the stakes.

Urban Shadows suggests that GMs “Jump straight to the good parts[...] Skip the boring stuff and focus instead on the core of what’s happening or what’s going to happen.” Regarding harder scene framings, Root says, “There’s no room for negotiation, no room to adjust and aim for a different kind of scene — the characters are in the scene, in that moment, dealing with that situation, and they have to react as best they can.”

From there on, the Framed Scene leaves player behavior to inertia, and often recommends the GM hold strong authority in terms of ending a scene in a timely way (See also: Cthulhu Dark, many PbtA games)

The Question Scene

This structure centers a dramatic question about the story or characters, usually a question that the table would like to explore as an unresolved point of thematic or narrative interest.

Orbital asks the player on their turn to create “a compelling story question,” then establish a foundation for the scene, and “continue playing until you feel the scene’s question is satisfactorily explored.” Microscope scenes begin with the question, written on an index card places in front of the players, and says that the “Question is why we are looking at the Scene in the first place, and the Scene isn’t complete until we find the answer.”

The Touchstone Scene

In these scenes, we are given an objective in the scene, such as something particular to say or include. This is our touchstone, a beat, phrase, or other story moment we must arrive at in order to say our scene is done.

In Dialect, a game about language, every scene indicates a particular invented word that every player must, at some point, say during the scene in a way that indicates their relationship to the word. In Cosmic Dark, players establish relationships with one another using flashback scenes that include a phrase at least one character must say. In Archipelago, players begin play by drafting “destiny points,” important story moments for players to eventually narrate in scenes.

The Process Scene

Process scenes are rarely included in games, but are effective. In the Process Scene, players have access to a list of step-by-step moments, prompts, or questions. Process scenes have clear beginnings and endings, and players know what they’re responsible for providing.

In The Quiet Year, a game about communities and collective projects, you can “Hold a Conversation” that includes the guideline: “Starting with you and going clockwise, everyone gets to weigh in once, sharing a single argument comprised of 1-2 sentences.” In Public Access, a game that involves a mysterious group of VHS tapes, players discover the contents of a tape by dividing up a list of prompts, and then narrating them one by one in order to flesh out the contents of the scene. (See also: The Between, DramaSystem, games with tactically rich combat)

The Dictated Scene

Simply put, these are scenes where one player or GM is given the opportunity to unilaterally narrate the events of a scene. These are also sometimes called “Minor Scenes,” and often exist in games to give a player an opportunity to write a piece of discrete fiction to complement the greater collaborative fiction. (See also: Microscope: Chronicle, Orbital, games where the GM is invited to “describe off-screen badness”)

Structures, launchpads, destinations — commentary on scenes and their approaches

Now I will reveal some of my personal biases. I find Foundation Scenes and Framed Scenes to be a great source of guidance. It’s in Process Scenes that I am currently seeing the most innovation and excitement.

So many common gripes or insecurities that come up around roleplaying, such as not knowing where to end a scene or not feeling capable of improvising with confidence, can find their source in a lack of structure. The great advantage of a prompt is that we know intuitively when a prompt is satisfied. The great advantage of a scene structure with a final step is that we know when we’ve reached our destination. Structures are comfortable containers that offer confidence and skillful behavior.

We might even say that combat in a game like D&D 5e or Pathfinder, laid out on a grid and mediated through ordered turns and action economy, is a sort of complex, maximalist Process Scene. Is it any wonder that players from these games often become curious about “mechanics for social encounters?” They are intuiting, correctly, that fights are simply scenes like any others, but have much more satisfying and inviting structures.

My belief is that most TTRPGs presume a baseline of very high capability in terms of dramatic ability and narrative instinct. More sharply: Our games presume and prioritize a certain personality type. This status quo simply leaves too many people behind, particularly players whose personalities or play styles thrive when offered structured opportunities for spontaneous creation, but withdraw when asked to do dramatic improvisation that they are not trained for. It is an accessibility issue and a design opportunity.

Lastly, a personal note: I am a boisterous and extroverted person, and I have a conservatory training in dramatic improvisation. My interest in scene structures comes from running games for people I love, but who may not have my personality or my training. I often see them struggle with this incredibly discreet slice of the roleplaying game experience. I have a big heart for them. I hope more designers will think deeply about what can be done to invite their participation and creativity. The players I encounter are hungry for greater innovation in formal scene structuring.

Over a decade ago, The DramaSystem from Pelgrane Press took this on in an interesting way, offering something like a foundation and then a process added on. Its dramatic scenes begin with information, but players are advised to center their roleplay around a rough process of dramatic challenges. It is possibly the greatest attempt I’ve seen at taking on the project.

If you are reading this post thinking to yourself, “I don’t see why any of this is necessary, I’ve never had any problem framing, developing, or improvising dramatic scenes at my table,” you should consider that this is probably a consequence of your talents and other skills, and that this exploration was written with people in mind who do not have your gifts.