How to schedule TTRPG sessions that actually happen, and play more games

Integrity. Adulthood. Cultivating friendship. And: Always have a session on the calendar.

“What makes us say of any discourse that it has or that it lacks ‘integrity’? Usually we can answer this in terms of whether such a discourse is really talking about what it says it is talking about.” - Dr Rowan Williams, 104th Archbishop of Canterbury, on theological argumentation

“Hey, we all know we’re busy adults.”

—Guy explaining why he thinks about D&D constantly but never plays it.

Look, sometimes I’m going to reflect on a game, or on design, or on community, or some essay about emergent phenomena in play. Sometimes I’m just going to give you a listicle. Today, it’s a listicle. Or a lesson-in-a-listicle. As always, I couldn’t help some of the spiritual/ideological slip through. Skip to the last section for the punch-line and a bit about adulthood and adult friendship. Here we go.

Buy-in is king. Almost all of the work of getting people to the table is to set clear expectations, get people to agree on them in advance, then deliver on those expectations with integrity. I’m going to say what I mean here by integrity, and then all of my advice. If you don’t like this next part, you might not like the rest of it, or at least you’re not going to think it’s possible:

Integrity is an essential ingredient in maintaining relationships — in life, and in gathering for play

By integrity, we mean something very specific here: “Integrity” is when something is about what it claims to be about. As per the quote up top, an argument has integrity when it is about what’s being presented, and isn’t secretly an argument about some unspoken other thing. A person has integrity when they proclaim “I will do something,” and then they make it happen.

If a person routinely makes a firm agreement to gather with you and then just-as-often cancels, that person has an integrity problem around scheduling. I’m not going to pronounce this as a form of personal failing or problem — that’s up to you and your friendships, and what you value.

But it is, without a doubt, a near-insurmountable organizing problem. If you set out to schedule games, but cannot address or even identify this integrity problem as it emerges in those around you, you will meet with failure, disappointment, and burnout.

All we can do is nurture and encourage integrity in one another. But it is something we must do to have more games.

Work the calendar

At the start of a campaign, sit down with your players, pop open your calendars, and get the first few sessions on the books. Even if it means looking months ahead, make sure you schedule that next session before you end your gathering, a date that everyone is totally happy with.

Always have one session on the calendar.

The best thing you can do to help your group meet is to make sure, for any game or campaign you’re running, that you have the NEXT session on the calendar.

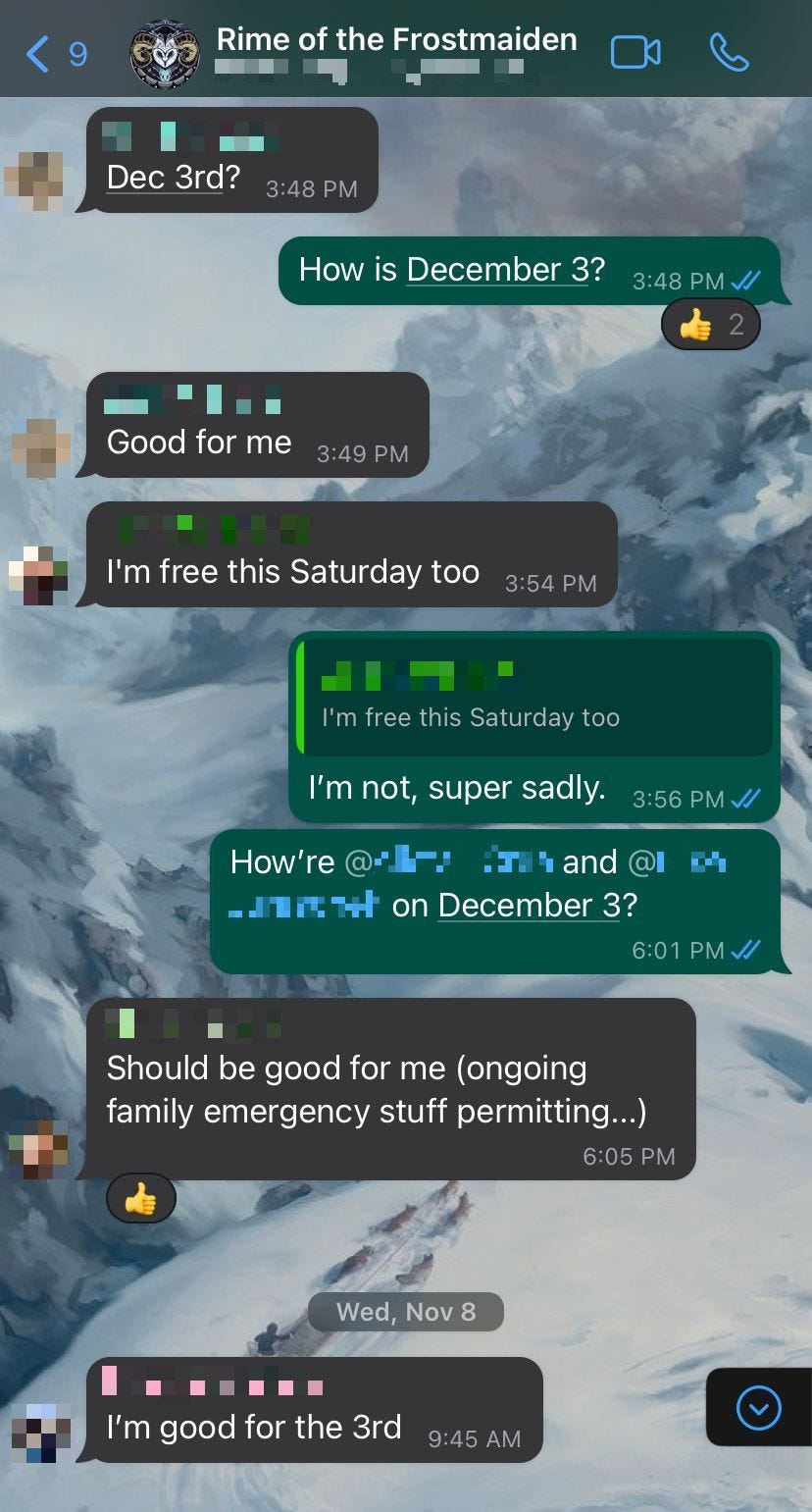

This is how you work the calendar: Get everyone’s attention, and get the calendars on the table. Pick a date. Can we make it? No? Pick the next date. Can we commit? No? Pick the next date. Is someone a “maybe?” Ask: “Can you make the commitment for now, try to keep it, and let us know as soon as you have to cancel?” Good enough.

Always have one session on the calendar.

If you can’t meet for 3 weeks, it’s better to find that out now and set that date in stone than to check in every week to hear “no, sorry, busy again” until you get demoralized enough that you learn to stop asking.

Your best friend in this effort is an online tool where you can throw out a bunch of dates and times and have your players click off which ones they are free so that you could find the best time for everyone. Here are two tools that can do this:

Doodle - It’s slick and has various tools for integrating calendar invites and such.

WhenIsGood - It looks fun and lite. It’s worth clicking around on. The name is impeccable.

If you have to cancel on the only date ya’ll have on the books, ping the group, start to work the calendar, and get the next date on the calendar, because your new policy is to always have a session on the calendar. The moment it comes through on the groupchat that Suzie can no longer make it on the 2nd of next month, you respond with, “Ok gang, how are the 7th and the 10th looking? Let’s get the reschedule done now.”

Also, use whatever calendar app you are already using for the rest of your life’s business (Google Calendar, Outlook, whatever) and send out the session to all players via invite. Always have two forms of record-keeping — a comms channel like group chat, and a scheduling channel like a calendar app or an email.

Someone will someday say to you, “Oh, I don’t look at the group chat often, I wish I had it as a GCal invite.” Head this off at the pass!

Ask your players what their biggest barriers are

Everyone has little scheduling barriers, the things that might make it tough for you to run a game. Measuring against one another to see who has it easier is a bullshit exercise. The fact of the matter is, everyone’s reasons are valid.

And for many of us, our reasons for being “busy” are also sources of shame. We hate to break it to our friends that we don’t want to schedule a game for reasons big (I’m caring for an ailing parent that day) and small (I just don’t feel like scheduling a game after an evening of grading papers, even if I’m free).

So: Ask your players up front “Ok, what typically gets in the way of your ability to schedule? What are your big barriers?” Make it clear to your players they don’t have to be ashamed, or embarrassed, and that you will work with them.

Here are the kinds of answers I’ve gotten in the past month:

“I have to travel for work for 5-7 particular days out of every month.”

“I can’t commit the whole evening, but rather a specific, narrow 2.5-hour window.”

“I would have to take a Zoom call from your apartment immediately afterward, and would need private use of a room in your home for that hour.”

“It feels like everyone wants to meet in your apartment, but I want to spend more of my free time outside these next few weeks.”

None of these are insurmountable. These people just need you to go “Got it. We will make it work.” Then, you work the calendar.

Stick to the agreed time, keep it tight, keep it reliable

Stick to the scheduled game time like your very life depends on it, and let all socialization happen before or after. Violate these boundaries, and most people won’t complain, but they won’t trust their own ability to commit to your sessions, and when this becomes the case, they will more strongly consider turning them down in the future.

I’ll lay it out: Some enchanted evening, you will gather your group for the good old 7:00-9:00pm session. Then, when it gets to 9:00pm, everyone will go “What the hell, let’s keep going! This is so fun, and we don’t have anywhere to be, right?” and on you’ll go until 10:30pm or even 11:00pm. This needs to happen exactly once, and from then on, your players will think of the weekly 2-hour game as an actually-3-almost-4-hour game. And the next time they really only have 7:00-9:00pm to commit to the game, something in their very bones will them that to turn it down for fear of having to leave “early.”

Keeping to time is also a way of ensuring that your game and your organizing has integrity. Bridges with integrity are bridges people will walk across.

As much fun as you’re having, end on time. End on cliffhangers, end in the middle of the fun. If people want to hang and chat, all the better. But the game must end when you say it ends. You got buy in. Honor that buy-in.

Run shorter campaigns, and name the commitment

We’re all daydreamers, seekers, imagineers, explorers. And we’re all tempted to run epic campaigns. But if you want to run more games, find campaign concepts that are closer to 8-12 sessions, as opposed to 20-30 sessions and beyond. Or even shorter!

Then, name that commitment up front, and see if everyone likes it and agrees. Even after they agree, ask again, like this:

You: “Ok folks, do we like the idea of running this other game? I’m thinking 4-6 sessions.”

Them: “Yeah, sure, sounds good!”

You: “So you agree that 4-6 sessions is good for this? That’s what we like, and what we find manageable?”

This is an extension of working the calendar, because buy-in is king, and it’s easier to get buy in on “Hey, can ya’ll commit to 3-4 sessions, booked in advance?” than it is to invite someone to “every one of your Sunday afternoons indefinitely.” Especially if you want to run new games! Running shorter experiments is always easier for running people through new systems.

It’s not: “Want to switch to a new system?”

It’s: “Want to try this other game for 3 sessions? Anyone who doesn’t want to can take a break! Then at the end, we’ll see what we want to do next.”

Smaller groups

Simple logistics here: It is simply easier to get 2-3 other people to commit to a date and get something on the books. It always gets more difficult the longer a commitment is, but a smaller group has much more longevity as well.

10 years ago, I would have said “Ugh, a game with a GM and just two players? Or even just one? Would that even work?” Now I just laugh to myself. A game between me and two players is a dream. I can’t think of an RPG these days that you can’t run with two players. These days, when it comes to co-op games and worldbuilding games, having more than three players can be game-breaking. What a fun new era to be a part of.

Here is an attendant principle I also believe in: Everyone must be there. Work harder not on creating a giant group where people can come and go, but a tight group that is accountable to show up. You’ll get consistent storylines, and when you take a week off, everyone takes a week off to breathe.

Maybe you want to run an open table, where everyone gets to come and go except for the GM, who is always-on. Go with God.

Cast a net

This is the simplest: Put out wide calls, run groups with new people and new kinds of people. Go into spaces and advertise your games. Don’t be afraid to mix it up.

Desperate to test a new system? Stop trying to recruit your current players and find new ones. Hit up the local Discord and just see who might be interested in the new game you’re running. You also never know who in your workplace might be interested, or in your building, or in your other communities.

Note: This is going to be my shortest section, because I have an entirely separate post to make about developing new players.

If the issue is that certain players are very enthusiastic to play a certain game or campaign, but you need a few extra players to join them, you can even deputize groups to organize themselves. Which leads to:

Deputize helpers

There is no reason that the DM has to organize the time, place, and other logistics. Delegate this to others.

“Well,” you might say, desperate to argue, “the GM has to do the scheduling because it’s essential that they be there, they’re managing the space.” This is silliness. Hypothetically: If me, you, and our friend Joe have to get coffee, any one of us can be the person whose job it is to pick out a cafe and propose times, even if Joe is, for some reason, the only one who obligated to be there.

This is especially true if it is a player-driven game. I currently have a player who wants to do a pirate-themed game that I am happy to GM, but not something that’s an organizing priority for me. My message was simple: You pick the place, find a time that works, pick your players, and gimme a week’s notice, and I’ll run that game for you any time. And then I left it alone. Will she do it? That’s up to her. I hope so!

If you cannot deputize others to do the scheduling, there are other jobs you can give away. Here are some things you can give away:

Let them work out food arrangements amongst themselves. Been doing this for years, and I’m very happy I don’t have to think about how to balance encounters and everyone’s food allergies in the same 10 minutes.

Worldbuilding tasks. If prep is murdering you, assign a magic items designer, and let them build. Anything you can give away, give away. It might feel bad to consider, but try it once and see how good it feels to look at the returns.

This goes against common wisdom, only because organizing skills have become too heavily concentrated on GMs. I remember the first time I listened to the Dungeons & Daddies, it basically cause my brain to glitch when I realized the host of the podcast was not the GM of the game — that this didn’t have to be the same person.

Why would they be?

Become a person who is serious about scheduling. Believe that scheduling a game matters, and is important for honesty and integrity

There is this thing with TTRPGs — maybe a function of insecurity around nerdiness, or a certain ironic stance toward one’s own interests? — where people just feel weirdly comfortable with the social standard that a TTRPG session is something nobody should have to accommodate or make time for, even when you’ve previously agreed to it.

We all have emergencies! But plenty of people make time, week in and week out, to simply not miss certain engagements with great regularity. Nobody would find it socially acceptable to cancel coffee plans, made well in advance, twice in a row or up-to-half of the time those plans are made, right? It’s just a baseline for being able to relate to one another that we keep those sorts of commitments. But it’s somehow simply normal for people to cancel on game groups in this way.

For me, part of my getting to play more games meant becoming a new kind of person.

“We’re all busy adults.” Busy adults keep calendars. Busy adults learn to make a commitment one month in advance so that they don’t have to cancel frequently. Busy adults add more tools to their toolbelt when they need help keeping commitments, because being where you say you’ll be is part of what being an adult-with-adult-integrity fundamentally means. Busy adults say “I want to remind you of what you agreed to.” Busy adults say this to themselves.

It’s actually an act of care to hold our relationships accountable in this way. Like establishing boundaries, affirming commitments is another way of saying “I want this relationship to work.”

(Tangentially, I wonder if the current epidemic of adult loneliness, and the crisis in U.S. adult friendship, has anything to do with the broader cultural inability to nurture these exact skills.)

Recently, when asked “are you ready for this week’s session?” one of my players said, “Oh no, I can’t anymore, I accidentally just scheduled something that day. Did we… was it really this week?” Personally, I wanted to balk and go “Yeah, haha no problem, it happens, we’ll just move the time.” Instead, I did something uncomfortable I didn’t really want to do, because it felt difficult:

I said, “Yeah dude, we all agreed three weeks ago that we’d hold this exact evening in our calendar. Like… that’s the night.” She responded, “Ok, sorry, yeah, I can move that other thing, it actually shouldn’t be a problem to keep the initial commitment. I’ll be there.”

I didn’t handle it this way to be a dick, or to be overly serious, or to push this person away or be stern or act like her Dad or whatever. On the contrary, I did it because I love this person, because I want to see them more often, and to sit across the table and roll dice with them. And now, we will.

PS: A note on open tables

You might read all this and go “The simple solution is to run an open table, where players don’t have to make commitments, but can just show up when they like.”

This fundamentally sets up a social dynamic where people consider their own participation less fundamental to group health, and this becomes a self-fulfilling prophesy. Tell people they can show up less, and they will show up less.

You know who doesn’t get to show up less? The GM. The math on open tables works out so that the GM de facto has less time off than everyone else, because they are the only person who is never taking off on game night. This reinforces a hierarchical/consumer dynamic wherein the GM is an always-on service provider who is ready and available when you make time to show up.

The above dynamic, once on display, will create two obvious tiers of participation. Good luck asking anyone who is a come-and-go player in this situation to ever want to switch to GMing.

The dynamic is anti-social, because it’s implicitly not mutual. Sure, you don’t have to hold people’s feet to the fire about making or keeping commitments, but, to belabor the point, making and keeping commitments is a self-perpetuating social good.

Quite simply, it all seems like a recipe for burnout.

I’m actually going to start podcasting soon. Or rather, I’m going to be doing YouTube videos and also some audio-only stuff that will go on YouTube and Spotify.

Until then,

turned me onto this stunning collection called “A Dozen Fragments on Playground Theory” that I’ve just been turning around in my head like a prism, trying to hold it up to the light and see what it brings up in me. I think it’s worth checking out.

> Here is an attendant principle I also believe in: Everyone must be there. Work harder not on creating a giant group where people can come and go, but a tight group that is accountable to show up. You’ll get consistent storylines, and when you take a week off, everyone takes a week off to breathe.

> This fundamentally sets up a social dynamic where people consider their own participation less fundamental to group health, and this becomes a self-fulfilling prophesy. Tell people they can show up less, and they will show up less.

Amen. I could go on and on about how vigorously I'm in agreement with this post, but I'll leave it at that for now.